At any given time, your brain and spinal cord are bathed in a little less than a half a cup of fluid. This clear and colorless fluid is called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and is very important to how your brain functions.

Your brain is quite heavy, weighing a little over 3 lbs; however, because it is actually floating in CSF, your brain isn’t affected by its own weight. Being suspended in CSF prevents the brain from crushing its own neurons and blood vessels.

CSF also acts as a cushion for the brain, protecting it from injury from a blow to the head. It also allows very important chemicals to travel to and from your brain cells. These chemicals are important for your brain function and if they are not able to flow freely, serious damage to your brain can occur. CSF also removes waste products produced by various processes in your brain.

In order to understand hydrocephalus, it’s important to first understand how cerebrospinal fluid and the brain’s ventricular system works.

Ventricles of the brain

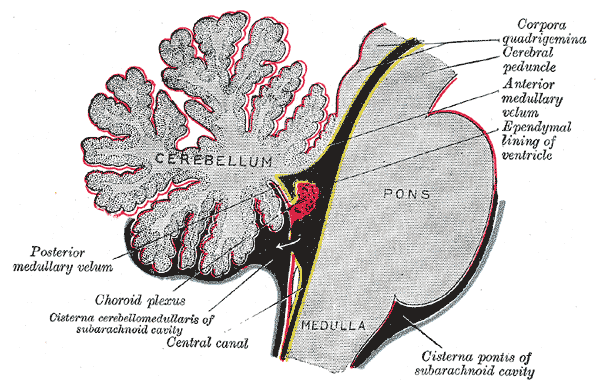

The ventricles of the brain are like small water balloons which support the brain from the inside. You have several ventricles in your brain. The main ventricles are the two lateral ventricles (one in each hemisphere), the central ventricle (known as the third ventricle), and the small fourth ventricle near the brainstem.

Together, these ventricles contain only about 7 teaspoons of CSF at any given time.

The ventricles of the brain

Where is cerebrospinal fluid made?

Most of your CSF is made inside of your ventricles in a special network of blood vessels and cells called the choroid plexus. The choroid plexus produces CSF quite slowly, replacing your CSF volume about 3 – 4 times each day.

What is hydrocephalus?

Hydrocephalus is the abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid either within the ventricles of the brain or in the space left behind after part of the brain is removed (known as the resection cavity). Although scientists do not know exactly why hydrocephalus occurs, most theories state that it is caused by an imbalance between the amount of CSF that is produced and the rate at which it is absorbed. As the fluid builds up, it causes the ventricles or resection cavity to enlarge which increases the pressure inside the head.

Pressure on the brain can result in short- or long-term effects, including impaired vision (such as blurred vision or difficulty seeing color), headaches, hearing loss, muscle weakness, seizure disorders, hormonal imbalances, problems with thinking and memory, and brain swelling. Untreated hydrocephalus poses permanent risks risks to both cognitive and physical development due to white matter damage, pressure on the hypothalamus, or other causes.

Left untreated, progressive hydrocephalus is usually fatal.

Check out this info-graphic for a quick overview of hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy and other epilepsy brain surgeries.

Do brain surgeries to stop seizures cause hydrocephalus?

Any time there is a change in the amount of fluid, brain matter, or blood in your brain, hydrocephalus can occur. We know that hydrocephalus can be caused by a stroke, brain injury, bleeding in the brain, meningitis, or when part of the brain is removed as in tumor removal surgery or certain brain surgeries to stop seizures.

For example, hemispherectomy surgery is known to cause hydrocephalus in approximately 23% of children who have the surgery. In this largest research study to date about hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy, it was found that 20% of patients develop hydrocephalus after functional hemispherectomy and 30% after anatomical hemispherectomy.

Very few research studies address hydrocephalus after other epilepsy surgeries. For other resection surgeries, like temporal lobectomy, the rate of hydrocephalus after surgery is reported as 2 – 6%. Although rare, hydrocephalus has been reported after VNS implantation.

What are the signs of hydrocephalus?

The most common symptoms of hydrocephalus include

- headache

- vomiting

- diminished level of consciousness

- sleepiness

- seizures

- cognitive decline

- behavioral changes

- vision changes

- papilledema (optic nerve swelling)

All symptoms do not have to be present in order for hydrocephalus to be diagnosed. In this large research study, where data from 690 children who had diagnosed hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy were collected, it was found that:

Only 44% had headache

Only 46% presented with vomiting

Only 43% had diminished level of consciousness

Only 80% showed changes to ventricle size on MRI or CT scan

Only 16% showed cognitive decline

Only 16% had behavioral changes

My child is not vomiting or tired, but has other symptoms of hydrocephalus. Should I be concerned?

Yes. Some children may have only behavioral changes or cognitive decline, such as trouble in school, as the first signs of hydrocephalus.

“Physicians may be reluctant to test for hydrocephalus after epilepsy surgery, especially if the child has been seizure free, and parents may need to be proactive in pushing for proper imaging.” – Dr. Gary Mathern, Dr. Alfonsina Q. Davies Endowed Chair in Epilepsy Research, Co-Director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Program, Professor, Departments of Neurosurgery and Psychiatry & BioBehavioral Medicine, Mattel Children’s Hospital, UCLA

My child’s MRI or CT scan shows that the ventricles “look good”. Do favorable imaging studies rule out hydrocephalus completely?

No. Unfortunately, imaging studies are not 100% reliable. In this large research study, only 80% of children had imaging changes. This means that 20% of the children had hydrocephalus with no changes in ventricle size since surgery on MRI or CT scan. Additional studies such as lumbar tap or intracranial monitoring may be needed to confirm hydrocephalus.

Are seizures a symptom of hydrocephalus?

Yes. Sometimes, the first symptom of hydrocephalus after epilepsy surgery can be seizures. Ask your neurosurgeon to first rule out hydrocephalus if your child has been seizure free after epilepsy surgery and suddenly has a new seizure. It is important to rule out whether the new seizure is from hydrocephalus.

My child does not have papilledema (optic nerve swelling). Does this rule out hydrocephalus?

No. Papilledema confirms high intracranial pressure, but does not rule it out. Research shows that children can have hydrocephalus without any optic nerve swelling, especially if the child is younger.

What are the chances of developing hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy?

Hydrocephalus occurs in approximately 23% of patients after hemispherectomy. 20% of patients develop hydrocephalus after functional hemispherectomy and 30% after anatomical hemispherectomy. More than one brain surgery where the skull was opened increases the changes of developing hydrocephalus.

Children with hemimegalencephaly have the highest risk of developing hydrocephalus, with the rate as high as 40% according to this study.

Hydrocephalus can develop ten or more years after surgery and shunts often fail.

Does the risk of developing hydrocephalus go down after surgery?

Unfortunately, the risk of developing hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy surgery never goes away. This study reports that the risk is highest 90 days or less after surgery, with 63% of children requiring shunts in the first three months after surgery; however, 27% of children develop hydrocephalus more than three months after surgery. The risk steadily drops thereafter and plateaus at about 8 years after surgery.

But the risk never drops to zero.

Children can develop hydrocephalus months or sometimes years after hemispherectomy surgery. One paper reports and adult developing hydrocephalus 36 years after surgery. Anecdotal reports from parents include children developing hydrocephalus five, ten, even fifteen years after surgery.

Research shows that long-term surveillance is necessary after surgery. This means that your child should be closely observed for symptoms even many years after surgery.

What is the risk of developing hydrocephalus after epilepsy surgeries like lobectomy, corpus callosotomy, or VNS implantation?

The risks of developing hydrocephalus after other epilepsy surgeries are approximately 2-6%.

What is the treatment for hydrocephalus?

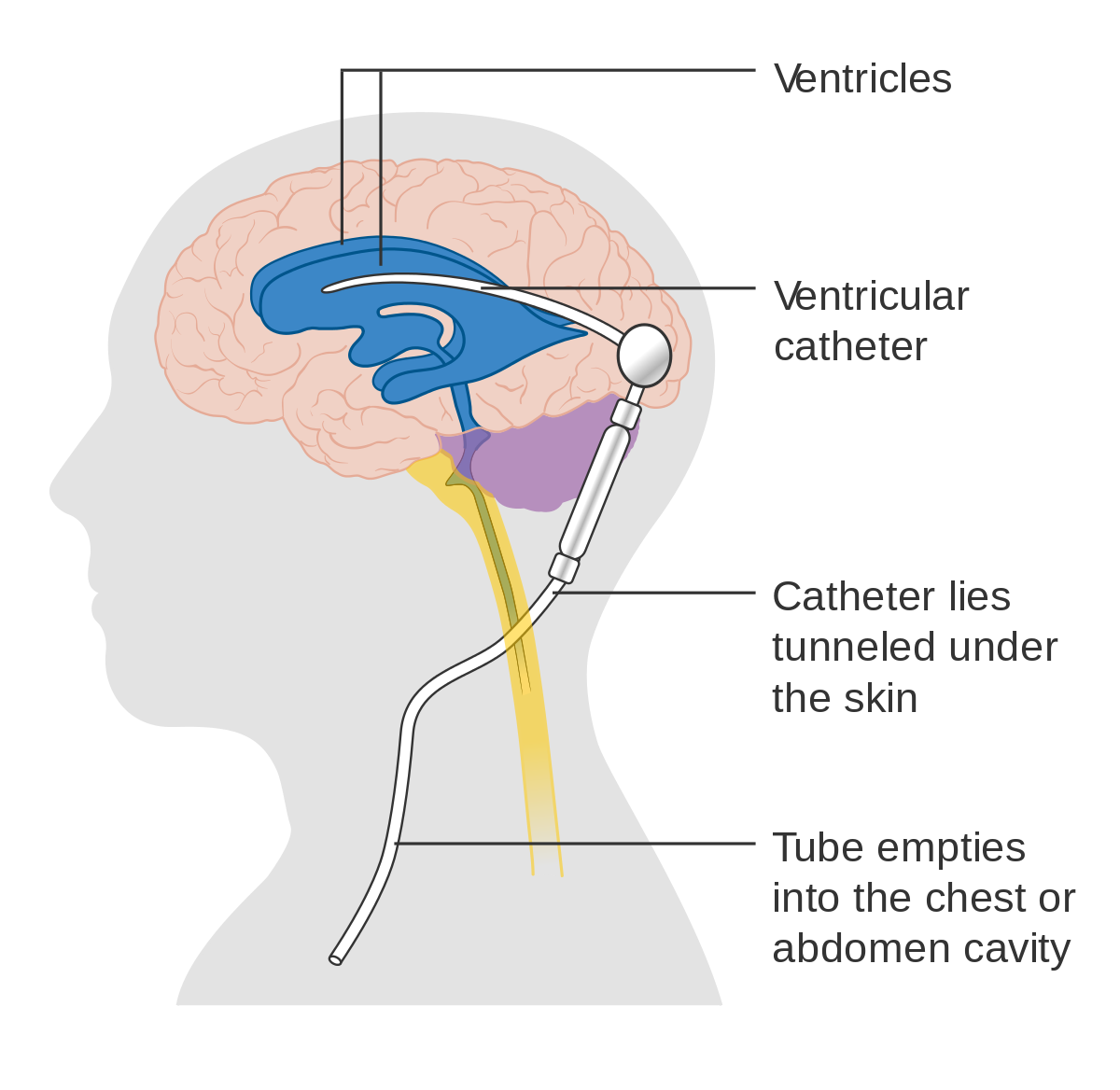

Hydrocephalus is a lifelong condition for which there is no cure. The most common treatment for hydrocephalus is a surgical procedure in which a tube called a shunt is placed into the child’s body. The shunt channels the flow of fluid away from the brain or spinal cord into another part of the bod) where the fluid can be absorbed and transported to the bloodstream. This reduces pressure on the brain, which if left untreated, can result in permanent brain damage or death.

- Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts moves fluid from the ventricles of the brain to the abdominal cavity

- A ventriculoatrial (VA) shunts moves fluid from the ventricles of the brain to a chamber of the heart

- A lumboperitoneal (LP) shunts move fluid from the lower back to the abdominal cavity

Shunts are extremely durable, and rarely fail or malfunction due to external causes such as falls or bumps. Almost all children with hydrocephalus can and should participate fully in all school activities, including physical education and most sports, with clearance from their neurosurgeon.

How long do shunts last?

Shunt systems require regular monitoring. When complications occur, subsequent surgery to replace the failed part or the entire shunt system may be needed. In fact, most people who have shunts will require shunt revision at some point in their lives.

Shunt systems have a very high failure rate. Approximately 30% of pediatric shunts fail in the first year, and most need to be replaced after ten years.

When there is reason to suspect that a shunt system is not functioning properly (for example, if the symptoms of hydrocephalus return), medical attention should be sought immediately. Generally, it is obvious when a shunt malfunctions. Signs of an overt failure would include recurring, intensifying headache and/or irritability, lethargy, nausea and/or vomiting with loss of appetite, and loss of the ability to look upwards. Subtle symptoms can also suggest a problem with the shunt. These would include an unexplained decline in school performance, pain or redness along the shunt tract, behavioral changes, or fever of an unexplained origin.

Should my child have a programmable or fixed valve shunt?

There are pros and cons to both devices which you should discuss with your child’s neurosurgeon. Shunt settings on programmable shunts can be changed easily without surgery, but they tend to clog more than fixed valves. Fixed shunts have a lower failure rate generally, but require surgery to change the shunt to a different shunt with a higher or lower setting if needed.

You can learn more about the various shunt systems on the Hydrocephalus Assocation’s website here.

Should the shunt be placed through the healthy side of the brain or in the resection cavity?

There is no consensus in the research regarding where the shunt should be placed. Some neurosurgeons shunt the remaining ventricle through the healthy side of the brain, while others shunt the resection cavity. Shunting the healthy side of the brain runs a risk of damaging healthy brain matter, while shunting the resection cavity runs a risk of brain shift in the event of over-draining of the shunt. The likelihood of these risks are unknown. Prior to shunt surgery, you should have a conversation with your child’s neurosurgeon regarding his/her experience with these risks and shunt placement preference.

Neuroanatomy of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Take a moment to watch this video which walks you through the anatomy of the ventricles and how your cerebrospinal fluid bathes your brain and spinal cord.

Hydrocephalus After Hemispherectomy And Other Resective Procedures

Dr. Aria Fallah, a fellowship trained pediatric neurosurgeon who practices at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital and Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center and Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery and Pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, discusses hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy and other resective epilepsy procedures at the 2017 Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Conference and Family Reunion.

Hydrocephalus After Epilepsy Surgery: Need To Treat Early?

Dr. Taylor Abel is the Surgical Directory of the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Program at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. He also sits on The Brain Recovery Project’s Scientific Advisory Board. Dr. Abel’s session discusses hydrocephalus, delay to diagnosis, post-hemispherectomy hydrocephalus, cysts, and fenestration, and management of the condition. There is an extended Q and A session with informative discussions as well.

Hydrocephalus After Hemispherectomy

Michael Handler, Chief of Neurosurgery at Children’s Hospital Colorado, discusses hydrocephalus after hemispherectomy at the 2016 Hemispherectomy Conference and Family Reunion.

Helpful Websites

Hydrocephalus Association Promotes a cure for hydrocephalus and aims to improve the lives of those affected by the condition. This website contains several fact sheets and guides to help readers understand hydrocephalus, various shunts and other interventions, and the impact of hydrocephalus on learning. The organization’s You Tube channel also provides extensive information about hydrocephalus.

Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network A consortium of researchers who conduct important and field-changing, multi-center clinical research to improve the lives of children living with hydrocephalus.

Hydro Kids A website offered by shunt manufacturer Codman which provides information about hydrocephalus and shunts.

Medtronic – What Is A Shunt? – Shunt manufacturer Medtronic’s web page which discusses their various shunt products, including anti-siphon devices.

Medline Plus This medical website includes detailed information about hydrocephalus.

Sources

Rossi, N., Jones, T., Lepard, J. Predicting shunt failure in children: should the global shunt revision rate be a quality measure? J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016 Mar;17(3):249-59.

Children’s Hospital at Montefiore: Neurological Disorders Hydrocephalus – Shunts

Georgiadis I, Kapsalaki EZ, Fountas KN. Temporal Lobe Resective Surgery for Medically Intractable Epilepsy: A Review of Complications and Side Effects. Epilepsy Research and Treatment. 2013;2013:752195.

Guénot M. Surgical treatment for epilepsy in children: indications and complications Rev Neurol (Paris). 2004 Jun; 160 Spec No 1:5S203-9.

Hydrocephalus Association. A teacher’s guide to hydrocephalus

Hydro Kids website: Signs that you may need a shunt replacement

Johns Hopkins Medicine Neurology and Neurosurgery website: Shunt Procedure

Lew S, Matthews A, Hartman A, Haranhalli N. Post-hemispherectomy hydrocephalus: results of a comprehensive, multiinstitutional review. Epilepsia. 2013 Feb; 54(2): 383–389.

Mathon B, Navarro V, Bielle F. Complications after surgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy associated with hippocampal sclerosis. World Neurosurg. 2017 Jun; 102:639-650.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke website: Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet.

Phung J., Krogstad P., Mathern G.W. Etiology associated with developing posthemispherectomy hydrocephalus after resection-disconnection procedures. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12:469–475

Pople I. Hydrocephalus and shunts: what the neurologist should know. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:i17-i22.